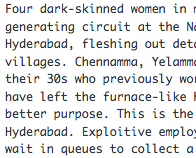

Four dark-skinned women in multi-hued saris hunch over a solar power-generating circuit at the National Institute for Rural Development (NIRD) in Hyderabad, fleshing out details about solar lamps and panels for Indian villages. Chennamma, Yelamma, Kalavati and Zayda, all illiterate women in their 30s who previously worked as stone crushers in South India’s quarries, have left the furnace-like heat of their previous jobs to use the sun

to a better purpose. This is the Women Barefoot Solar Engineers Association of Hyderabad. Exploitive employers, 10 hours of backbreaking labor and a long wait in queues to collect a wage of a dollar a day pretty much summed up these women’s bleak existence in the quarries. But today, after the institute’s Rural Technology Park helped train them as solar engineers, the women manufacture and maintain solar lamps and travel across India’s vast rural landscape to install solar power generators.

The transformation began in 2002, when Bunker Roy paid a visit to the rural development office. Roy is a social worker and founder of the Barefoot College and the Social Work and Research Centre in Tilonia, Rajasthan, an NGO that helps the poor to become economically independent. Roy suggested that the institute in Hyderabad work with the Barefoot College to train village women in assembling solar lamps.

The four women were chosen as Roy’s first batch of trainees. Between 2002 and 2004, the group made several trips from south central India to Rajasthan in the far northwest to become qualified solar engineers. “It was a life-changing experience for us,” says Chennamma, 35, who has four children and a husband who still works as a stone crusher. “We now earn double what we used to and are looked upon with great respect in society.”

It wasn’t easy. As they were neither literate nor conversant in Rajasthan’s local language, the group was tutored by a bilingual team at the Barefoot College through color-coding and sign language. They learned how to fabricate charge controllers, install invertors, assemble solar lanterns and lights, fix solar units in individual houses and then finally to establish a connection. The training took about six months.

“Often,” said Kalavathi, 36, “we’d lose heart during our training because we’d never even been near a school. But then we’d muster courage, encourage each other and carry on with our tough curriculum. What helped was that we never lost sight of our goal which we knew could better our own lives plus that of other poor people.”

Within six months of their return, on June 9, 2005, the four women – helped by the rural development institute – launched India’s first Women Barefoot Solar Engineers Association, registered in Hyderabad. Chenamma became president, Zahida its vice-president while Yellamma was designated treasurer and Kalavathi, the general secretary

Their first project entailed installing a five-kilowatt solar power plant at the Rural Technology Park itself. They set up solar panels, a battery bank and a workshop, providing power to electrify 15 houses in the park and 20 streetlights of 11 watts each in the Rural Building Centre, besides computers, printers and coolers.

According to Dr. Senthil Vinayakam, the technology park’s project director, “We were simply amazed at how confidently these women went about the task of setting up the solar power plant. It was an inspiration for many.” Apart from executing solar lighting projects, Vinayakam said, the newly minted solar engineers are also training other underprivileged women to become solar engineers. The group is also maintaining a Solar Energy Power House on behalf of the institute and they have completed work on lighting up other parts of the campus.

Besides installations, last year the women engineers also traveled south to Paderu Mandal in Vishakhapatnam to help 124 village households get solar power and establish a one-kilowatt powerhouse for street lighting. “Nothing beats the satisfaction of lighting up a village,” exults Chennamma. “When light suddenly floods the dark, dingy hut of a poor villager, the smile on his face is indescribable!”

Indeed in a country where 23 percent of 586,000 villages and 56 percent of 138 million households do not have electricity, Chennamma and her colleagues are literally bringing hope to hundreds. Analysts say that electrification in some remote areas, especially in distant and hilly terrain, is usually not technically or economically viable. Moreover, transmission and distribution costs of electricity in the country are prohibitive, making it unaffordable for about a quarter of India’s 1.3 billion people, many of who subsist on 20 cents a day, to afford electricity.

There is also faulty distribution to contend with. In India, voltage often plummets dramatically at the end of a long line due to a low load factor. In such a scenario, decentralized power generation systems ? based on alternative energy sources – are a better and more viable option to fulfill at least some residential and commercial demand for electricity.

Chennamma and her teammates, who now number 12 and growing, now run a production, training and maintenance facility at the rural development institute. The women produce solar lanterns, home lighting systems, streetlights, and water pumps. They have so far assembled 1,500 solar lamps, costing Rs 3,500 a piece.

“It takes two days to assemble one lamp,” says Kalavathi. “We also prepare small solar power circuits almost daily.” The small lamps are sold in the local markets while the larger ones (pegged at Rs 13,500) are supplied to industrial units. We give a guarantee of two years on lamps, which also ensures follow-up and after-sales services.

Impressed by the barefoot women engineers, the Andhra Pradesh Tribal Power Company Ltd commissioned the group to provide solar energy to the tribal hamlets of Pusalapalem and Thamingula last year. Chennamma and her team coached the local women in the maintenance of the solar systems. The solar power generated in these households is enough to power two 40 watt bulbs, one fan and one TV set for five hours a day. Each household that has a solar connection pays Rs 1,000 in installation charges and Rs 100 a month for maintenance. The money is entrusted to a village energy and environment committee.

According to Dr. Vinayakam, the experiment has successfully demonstrated the feasibility of training the poor to provide a vital development system. “It also underscores the fact,” he said, “that these people can be successfully entrusted with the management, control and ownership of such a sophisticated technology.